Music in Healthcare Settings Conference: Derby, 16 July 2015

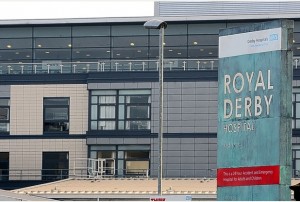

Thursday 16th July 2015, 9.30am – 4.30pm Education Centre, Royal Derby Hospital, Uttoxeter New Road, Derby, UK.

Thursday 16th July 2015, 9.30am – 4.30pm Education Centre, Royal Derby Hospital, Uttoxeter New Road, Derby, UK.

We are delighted to launch the forthcoming International Music in Healthcare Conference, hosted by OPUS Music CIC in partnership with Royal Derby Hospital and Air Arts to Aid Wellbeing.

Bringing together music for health practitioners, healthcare staff, promoters, funders, researchers and other key stakeholders, this event promises to provide stimulus for discussion and debate around the ongoing development of Music in Healthcare settings across the UK and beyond.

A mix of thought-provoking presentations and discussion groups throughout the day will leave all stakeholders with new contacts and new ideas for continuing to develop their own practice.

Places are available to book for a modest charge of £10 from the Eventbrite link below (includes tea and coffee on the day).

We are also hosting a Music in Healthcare Settings ‘Music Sharing’ day on Friday 17th July 2015, to be held in Derby. Any musicians attending the conference are invited to come along from 9.30am-3.30pm (stay for as long or short a time as you like!) to make music with like-minded musicians (small charge of £2 payable on the day to cover refreshment costs).

Please email us at conference@opusmusic.org if you would like to come along to the Music Sharing day.