OPUS Music’s Compassionate Contribution to End-of-Life Care

OPUS Music’s Compassionate Contribution to End-of-Life Care

This October the 14th the world comes together to observe World Palliative Care and Hospice Day, and we shine a spotlight on the transformative role of music in providing solace and comfort during the most delicate moments of life.

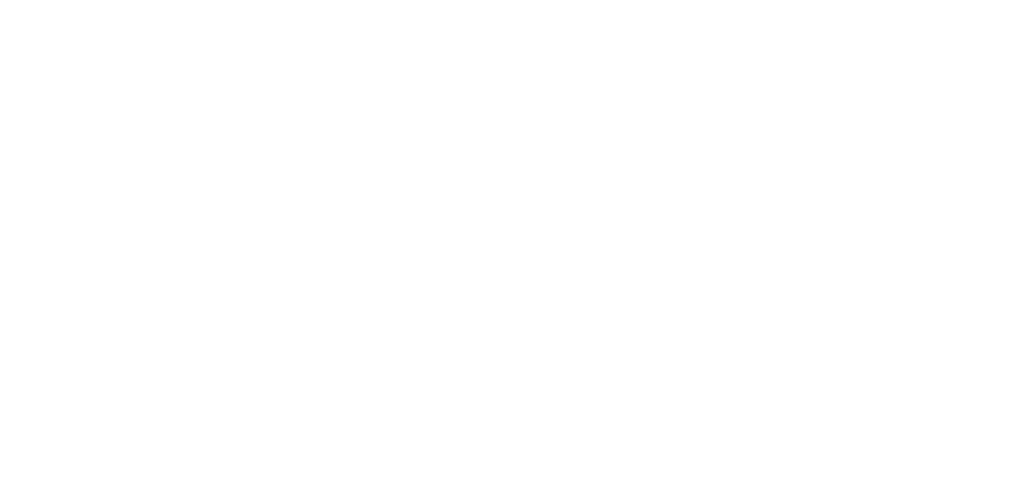

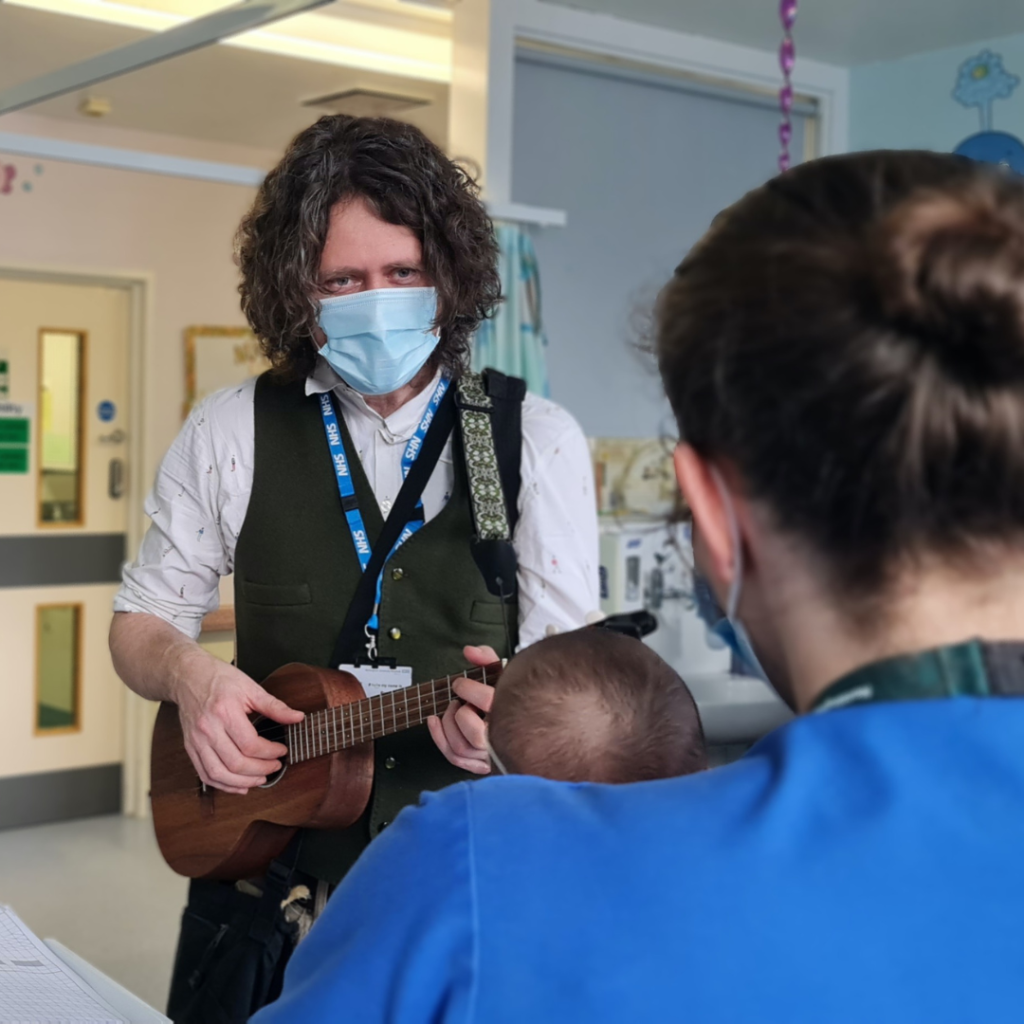

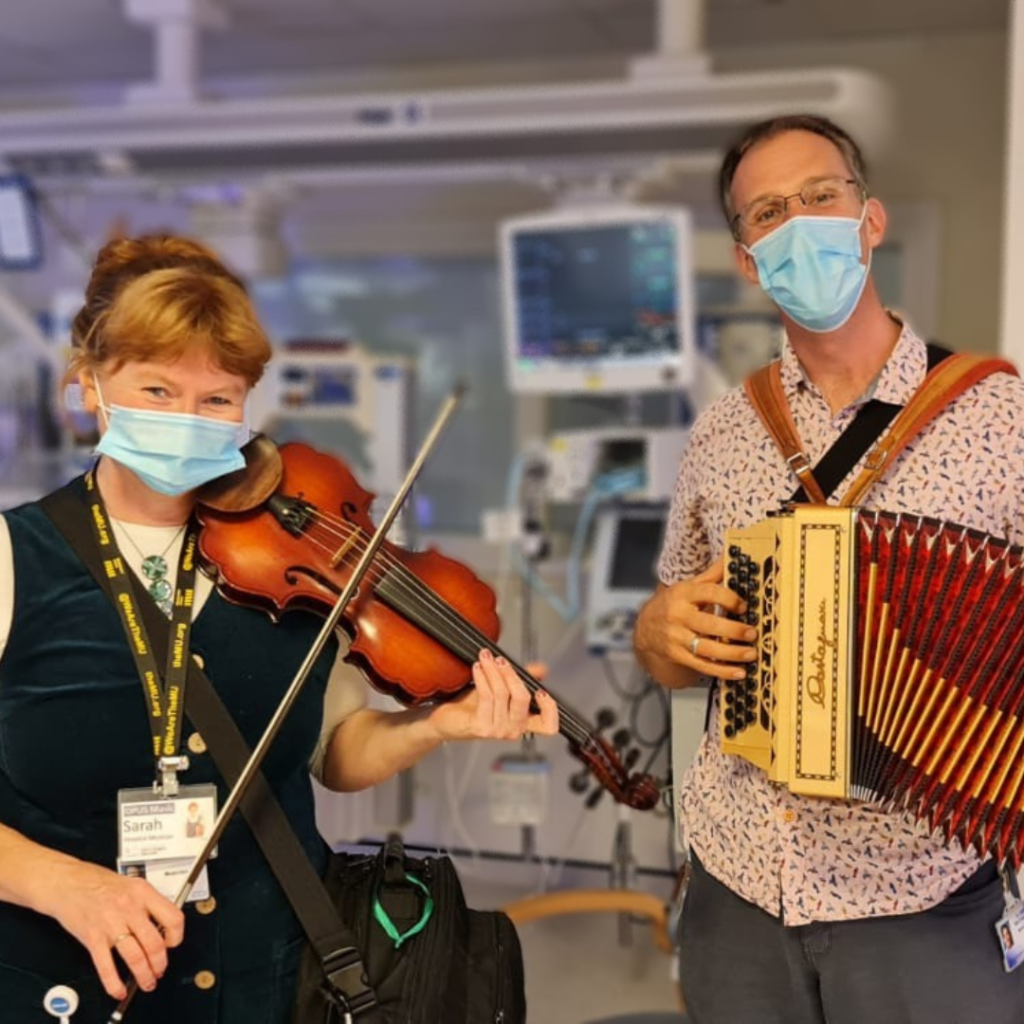

At OPUS our ethos is to make music with all to promote positive health and wellbeing. These music-making sessions explore connection, remove communication boundaries, and promote the health benefits that music brings. Supporting not only the patient, but the family, and healthcare staff that surround them at these significant times. Music offers the space for emotional release, to soothe, and to support connection, which is vital in these last moments.

“I want to thank you OPUS for yesterday. You played beautiful songs, and my Mum sang, smiled, and loved it. Mum passed away early this morning. We are devastated, but remembering the smile on her face whilst watching you will stay with me always!” – Daughter of a patient

As well as working in hospitals across the East Midlands, we also make music in community settings, in hospices, and care homes, bringing music to individuals. The feedback we have received from family testimonials highlights the significance of music in end-of-life care.

We believe that compassion in action within the realm of end-of-life care is vital, and we understand the important role that music can play in these final moments. Our healthcare musicians enter patient rooms with sensitivity and grace, crafting musical moments that transcend the ordinary. Our aim is to facilitate solace and connection to patients and their families during a challenging time.

“Thank you for playing to my mum while she was a patient. You came into her room and played beautifully, such a magical moment we will never forget, thank you.” – Son of a patient

In the hushed corridors of hospices and hospitals worldwide, where the journey of life meets its final notes, music resounds as a healer and the bridge to connection, creates lasting final memories. As we celebrate World Palliative Care and Hospice Day, we join the conversation and champion the transformative power of music in end-of-life care. Our impact extends beyond hospices and hospitals; it reaches into the hearts of patients and their families, creating lasting memories.

The profound impact of music emerges as a universal language that transcends words, easing pain, offering solace and leaving an enduring legacy of compassion and connection.

Find out more about what we've been up to...

Music as a Social Prescription

Music reaches people in ways that traditional interventions sometimes cannot. It creates spaces

The Sound of Integrated Care

The Sound of Integrated Care: Why Music Belongs in Every Health Setting

We are Hiring a Finance Manager at OPUS

OPUS music are hiring a new Finance Manager to work with the team

Celebrating International Music Day 2025

Chris & Marianne’s Story A Journey of Hope and Healing Music has the

OPUS Music CIC Wins Community Partner of the Year

OPUS Music CIC Wins Community Partner of the Year at Sherwood Forest Hospitals’